New York, not unlike other cities in America, has a race problem. The problem is manifested by outbreaks of racially-motivated violence and by patterns of decision making — both individual and institutional — that has entire neighborhoods polarized and demarcated by race. A city with a world-wide reputation for its diversity and multi-cultural character is nonetheless seemingly torn asunder by racial rivalries and intergroup strife.

New York, not unlike other cities in America, has a race problem. The problem is manifested by outbreaks of racially-motivated violence and by patterns of decision making — both individual and institutional — that has entire neighborhoods polarized and demarcated by race. A city with a world-wide reputation for its diversity and multi-cultural character is nonetheless seemingly torn asunder by racial rivalries and intergroup strife.

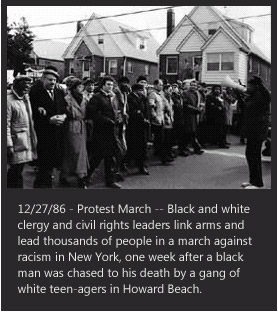

In Crown Heights, Brooklyn, for example, Hasidic Jews and Caribbean blacks are in conflict. In 1991 riots ensued on the streets of Crown Heights, and blacks and Jews, perhaps for the first time in American history, were in physical conflict. Canarsie is yet another neighborhood in transition. Canarsie has been hit with fire bombings of real estate agencies that rent to minorities, and beset with intergroup conflict, including racial violence between some Italians and blacks. Howard Beach, in Queens, was the site of racial violence in 1986, with the slaying of Michael Griffith, a 22-year-old black man who was chased on to a highway by a gang of whites. And in 1989,

Yusef Hawkins, a 16-year-old black youth was murdered by whites in the predominantly white section of Bensonhurst.

Other New York communities have experienced racial strife involving attacks on minorities, including attacks on Jews, Asians, and homosexuals. These neighborhoods are in Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island. No New York borough has been spared such outbreaks of hatred. As one observer put it, “There’s been no improvement. If anything, people’s attitudes have gotten worse. What I see happening — incidents of racist behavior in the suburbs, on Staten Island, in Queens and Brooklyn — I don’t think we’ve scratched the surface of overt racism [in New York]…” (New York Newsday, October 11, 1992, at page 5)

The public education system is in crisis and suffering from low morale on the part of students, teachers and parents. Now with a majority non-white and largely poor student population, the City has been wrestling with controversial strategies designed purposefully to serve this new majority. Disputes over “multicultural education” and new minority-geared schools have questioned anew the melting pot theory of public education and of mainstreaming as a method of overcoming poor academic performance and low self-esteem on the part of low-income and non-white students. With the demographic changes in the public schools, local pressures have pushed school officials to experiment with Afrocentric and other ethnic approaches to public education; interaction and cultural exchanges between minority groups have been complicated by intergroup suspicion and rivalries, as well as by segregated housing patterns and peer-group socialization.

Racial prejudgments and “race-trait characteristics” have figured in the setting and articulation of educational policy as well as in the marketplace that influences housing choices, social contacts, and the administration of justice, including police/community relations. Today, black children who enter previously all-white New York neighborhoods are likely to be met with racial animosity, whereas in the recent past, in some parts of the country, they were spat upon and struck by whites who resisted school integration. Moreover, minorities are often in conflict with other minorities. For example, on Church Avenue in Flatbush, Brooklyn blacks and Koreans were in conflict. A secondary racial boycott ensued against Korean-owned groceries, allegedly in response to a reported racial insult of a black customer by a Korean merchant. The boycott was spiked by appeals to racial solidarity, and included vile, racist leafletting and chants.

Thus, the fight against bigotry today is both similar and qualitatively different from the campaigns waged in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Blacks and their allies once worked for a racially-neutral society; today, significant numbers of blacks and other ethnic groups favor racial preferences as the method for group advancement. After more than thirty years of steady progress in advancing racial integration and harmonious race relations, prejudice and acts of bigotry against minorities have not yet abated. Indeed, in New York City, hate crimes directed against minorities have, in recent years, been on the increase. The New York City Police Department’s Bias Unit reports that in 1991 there were 525 bias attacks. Included in those attacks were 169 anti-Semitic incidents; 118 against blacks; 67 against whites; 36 against Latinos; 18 against Asians (including East Indians); and 87 against gays. Six hundred and twenty seven bias incidents were recorded in 1992, including 211 anti-Semitic incidents; 103 against blacks; 130 against whites; 36 against Latinos; 27 against Asians; and 86 against gays.

Various sectors of society have been challenged and mobilized to respond to this crisis in human/race relations — government, the schools, the business community, community-based groups, religious institutions, civic associations and civil rights organizations. Their responses have been largely uncoordinated partly because of sharp differences among the groups about objectives, policies and strategies. Yet blacks in general and the civil rights community in particular are regarded by many as homogeneous and singular in their outlook. And those who disagree with once conventional approaches or with the ideological trends toward nationalism and racial balkanization have been the targets of name-calling and even accused of helping to destabilize the black community. The results of this balkanization have been disastrous for the civil rights movement. Hence, in Howard Beach, it might have been understandable or predicted that the protesters of the racially-motivated attacks against blacks would be blacks; that those condemning primarily anti-Asian violence in Flatbush, and in Borough Park, would be other Asians; and those objecting to anti-Semitism across the city would only be Jews. But the protesters of racial violence in such incidents were multi-racial, largely because of the existence and interventionist charter of the New York Civil Rights Coalition.

The New York Civil Rights Coalition was formed as the “New York City Civil Rights Coalition,” to bring together all people of good will to oppose publicly and consistently all forms of bigotry. Founded in 1986, a then loose confederation of civic and community-based organizations joined forces as the “New York City Civil Rights Coalition” to march in Howard Beach and to stay together afterwards to work purposefully on behalf of racial harmony and intergroup cooperation on specific civil rights campaigns. These groups came together as a result of a “Call” from six conveners that formed the Steering Committee of the Coalition: the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), the Asian-American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (AALDEF), the New York Urban League, the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund (PRLDEF), the Research and Advocacy Center for Equality (RACE), and the Law Students Civil Rights and Research Council (LSCRRC). The objective was to reduce an ethnically-polarized civil rights effort, to rekindle the spirit of multi-racial, joint actions to defeat race-baiting hatemongering and the divisive forces of defeatism, despair and racial separatism. In 1991, the New York City Civil Rights Coalition was reorganized by executive director Michael Meyers into the New York Civil Rights Coalition: a multi-racial network of concerned individuals who work cooperatively and with allied organizations on behalf of racial harmony, integration, and social progress. The New York Civil Rights Coalition is a 501(c)3 not-for-profit, non-partisan, tax-exempt, charitable organization, governed by a board of directors of distinguished citizens.